Psychologist Leo Ruickbie writes in “The Ghost in the Time Machine,” his 2021 prize winning essay in a competition sponsored by the Bigelow Institute for Consciousness Studies:

|

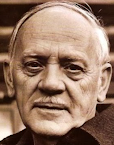

| John Barker |

In December 1966, psychiatrist John Barker contacted Peter Fairley, science editor of the London Evening Standard, with a plan to establish a clearing house for predictions, the Premonitions Bureau, using the Evening Standard to solicit premonitions from the general public in order to prevent future tragedies like Aberfan. Fairley agreed, giving Barker twelve months. The Premonitions Bureau went live in January 1967, receiving 469 premonitions in its first year. Several were deadly accurate.

The first was from Alan Hencher. He telephoned the Bureau at 6 am on March 21, 1967, telling Barker about an aeroplane crash “over mountains,” with high fatalities: “There are one hundred and twenty-three people, possibly one hundred and twenty-four.” On April 20, a Globe Air Bristol Britannia aeroplane carrying 130 people crashed into a hillside south of Nicosia Airport in Cyprus. The Evening Standard’s frontpage headline was “124 Die in Airliner” – two more subsequently died in hospital. It was Cyprus’s worst aircrash.

On April 23, 1967, Lorna Middleton contacted Barker: she had seen an astronaut looking “petrified, terrified and just frightened.” On April 24, Soviet cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov died when parachute failure caused his Soyuz capsule to smash into the ground at full speed. Hencher and Middleton again felt disaster loom towards the end of 1967, with Middleton describing a vision of a crowd and a railway platform, and seeing the words “Charing Cross,” a busy station in London, on November 1. On November 5, the Hastings to London Charing Cross train derailed near the Hither Green rail depot, killing 49 and injuring another 78. “Quite honestly it staggers me,” Barker told the Evening News afterwards, with the newspaper adding, dramatically, “Somehow, while dreaming or awake, they can gate-crash the time barrier.”

In Spring, 1968, messages started coming in to the Bureau of another impending tragedy. Middleton wrote “There may be another assassination. It may be in America shortly,” whilst telling a journalist that “The word assassination continues. I cannot disconnect it from Robert Kennedy.” Joan Hope in Canada wrote “Robert Kennedy to follow in his brother's footsteps.” On June 4, Middleton wrote again to the Bureau: “Another assassination and again in America.” On June 5, Miss C.E. Piddock in Kent wrote in her diary “Janitor will die today” – she later realised that “Senator” must have been meant. In the US, Alan Vaughan wrote to Dr. Stanley Krippner at the Maimonides Medical Center, with the warning that “This dream may presage the assassination of a third prominent American, one who had connections with John F. Kennedy [...] Could that other martyr be Bobby Kennedy?" Robert F. Kennedy was mortally wounded in a hail of bullets at the Ambassador Hotel, Los Angeles, at around midnight on June 5, 1968, dying in hospital the next day.

The Premonitions Bureau was scoring remarkable hits – its success had inspired Robert Nelson to start a similar operation in the USA, the Central Premonitions Registry – but there were dark clouds on the horizon. At the same time as the Cyprus plane crash, Hencher started to receive premonitions that Barker’s life was in danger. Hencher’s warnings persisted into 1968. Now Middleton was having troubling premonitions about Barker. On February 7, she had a vision of him – just his head and shoulders – with her deceased parents: “my parents were trying to tell me something,” she said. Barker suffered a brain haemorrhage on August 18, 1968, dying later in hospital.

Leo Ruickbie, “The Ghost in the Time Machine,” his 2021 prize winning essay in a competition sponsored by the Bigelow Institute for Consciousness Studies. Ruickbie teaches psychology at Kings College and the University of Northamptom in the United Kingdom. Footnotes have been deleted from these online excerpts from his essay. The entire essay may be downloaded at the Bigelow site https://bigelowinstitute.org/contest_winners3.php.