Greg Taylor writes: One group that conducted detailed, skeptical investigation of mediums – for many decades, starting in the late 19th century – was the Society for Psychical Research (S.P.R.), who as we have already seen also carried out research into ‘crisis apparitions’ at the time of death. The S.P.R. has included in its ranks some of the finest scientists, academics and public figures of their time, along with plenty of skilled investigators who in many instances had an understanding of magic tricks and the techniques of fake mediums.

While, through their skills, they certainly outed their share of frauds, the S.P.R.’s investigators also uncovered a number of mediums who consistently communicated information that was highly suggestive to them of the survival of consciousness. One of those mediums is now considered as perhaps the most tested of all time, and possibly offers the most substantial collection of evidence for the survival of consciousness collected thus far: Leonora Piper.

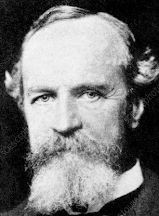

The prodigious talents of Leonora Piper were first uncovered by Professor William James of Harvard University, one of the most highly regarded thinkers of the 19th century (his texts Principles of Psychology and The Varieties of Religious Experience are classics in their respective fields). James had an interest – if a rather skeptical one – in the claims made by Spiritualists of communication with the dead, so when his wife’s family told him about an extraordinary trance medium they had visited in Boston, he thought it might be worthwhile to investigate further.

Ever the skeptic, James was careful to ensure that Mrs. Piper did not know who he was when arranging the visit and was wary of assisting the medium through any cold reading attempts, taking “particular pains” to not give Piper’s ‘control’ personality any “help over his difficulties and to ask no leading questions.” And yet the entranced Mrs. Piper consistently produced extremely accurate private information that James found convincing. “My impression after this first visit,” James later noted, “was, that [Mrs. Piper] was either possessed of supernormal powers or knew the members of my wife’s family by sight and had by some lucky coincidence become acquainted with such a multitude of their domestic circumstances as to produce the startling impression which she did.” While his skeptical nature is obvious in the caveat in this initial summation, continued visits with Piper subsequently led him to “absolutely to reject the latter explanation, and to believe that she has supernormal powers”:

I am persuaded of the medium’s honesty, and of the genuineness of her trance...I now believe her to be in possession of a power as yet unexplained.

On the basis of William James’ opinion of Leonora Piper, the S.P.R. assigned one of their toughest skeptical minds, Richard Hodgson, to the case. Hodgson had made his name with a high-profile debunking of the leader of the controversial Theosophical movement, Helena Blavatsky, as well as papers pointing out the poor observational ability and gullibility of sitters at séances. “Nearly all the professional mediums,” he had scowled in one report, “are a gang of vulgar tricksters who are more or less in league with one another.” Hodgson ended up investigating Leonora Piper for almost twenty years, using detectives to shadow her and her husband, arranging sittings for others anonymously, and taking numerous other precautions, while transcribing the information produced and checking it carefully. To test whether Piper was truly in a trance, Hodgson pinched her suddenly (“sometimes rather severely”), held a lit match to her forearm, and forced her to take several deep inhalations of ammonia (another researcher poked her with needles without warning). The entranced Piper showed absolutely no reaction to these tests – though, as Hodgson rather coldly noted, she “suffered somewhat after the trance was over.”

Hodgson collected thousands of pages of testimony and analysis, and reams of evidence suggesting that Leonora Piper had access to information beyond her normal senses. While it is impossible here to properly transmit the collective weight of the evidence produced during such a detailed, careful investigation over an incredibly long period of time, Hodgson’s official conclusion should at least offer some idea of its effect. The scrupulous investigator, who had started his research with unbridled skepticism, was now, he said, convinced “that the chief ‘communicators’...have survived the change we call death, and... have directly communicated with us...through Mrs. Piper’s entranced organism.”

The opinions of Richard Hodgson and William James on the mediumship of Leonora Piper were in no way outliers. Professor James Hyslop , another of the S.P.R.’s skeptical researchers who devoted a number of years to studying Piper, concluded that her mediumship provided evidence “that there is a future life and persistence of personal identity.” Frederic Myers, one of the founding members of the S.P.R., said of his own sittings that they “left little doubt – no doubt – that we were in the presence of an authentic utterance from a soul beyond the tomb.”

Leonora Piper was hardly the only focus of the S.P.R., however. They investigated many other mediums, and outed some as frauds, but also found a significant number of cases of mediumship to be evidential of the survival of consciousness. For example, another trance medium who impressed the S.P.R. was Gladys Osborne Leonard. Like Leonora Piper, Leonard allowed herself to be studied by the S.P.R. for a large portion of her life, from just prior to the First World War until after the Second World War had come to an end. And as with Mrs. Piper, the S.P.R. applied a skeptical attitude to their investigation, to the point of having detectives shadow Mrs. Leonard to determine if she was researching sitters’ details.

Again, the conclusion of investigators was that Leonard possessed some sort of supernormal power. A skeptical researcher who asked for one particular set of sittings – classical scholar E.R. Dodds – was left with no rational explanation for the information received. In contemplating the summary of the sittings – of 124 pieces of information given, 95 were classified under ‘right/good/fair’, and only 29 as ‘poor/doubtful/wrong’ – he noted that “the hypotheses of fraud, rational influence from disclosed facts, telepathy from the sitter, and coincidence cannot either singly or in combination account for the results obtained.” The experiment, he said, seemed to present investigators with a choice between two conclusions that were equally paradigm-shattering: either Mrs. Leonard was reading the minds of living people and presenting the information so obtained, or she was passing on the thoughts of minds “other than that of a living person.” Dodds concluded that he could see no plausible explanation that would allow his skeptical mind to escape this “staggering dilemma.”

Looking back on the many decades of research done by the S.P.R. since the late 19th century, it is quite extraordinary to note that these positive findings by diligent, skeptical researchers – as mentioned already, some of the finest minds of their time, who undertook detailed, long- term investigations of mediumship – and their larger conclusion for what it means for the survival of our consciousness beyond physical death, have simply been ignored by mainstream science.

Greg Taylor, “What is the Best Available Evidence for the

Survival of Human Consciousness after Permanent Bodily Death?” An essay written

for the Bigelow contest addressing this question. I am presenting excerpts

without references, but this essay is available with footnotes and a

bibliography at https://bigelowinstitute.org/contest_winners3.php.